Areas

Smarter wildlife recording

It hasn’t taken long for wildlife recording to embrace the power of the smartphone technology at our finger tips. Visit the android or apple app stores and you will find hundreds of wildlife related apps; this article will help you find some of the most useful ones aimed at helping you to identify, record and share your wildlife records.

Smartphones have an obvious benefit for logging wildlife records – your phone immediately knows three of the four Ws essential for a wildlife record (when, where and who) and a basic record can be quickly created simply by entering the ‘what’ – a species name – from a list on the app. So what’s currently on offer, and which ones should you use? Here are a few pointers to some of the most useful apps, focussing primarily on those with a core wildlife recording element.

Multi-taxa apps

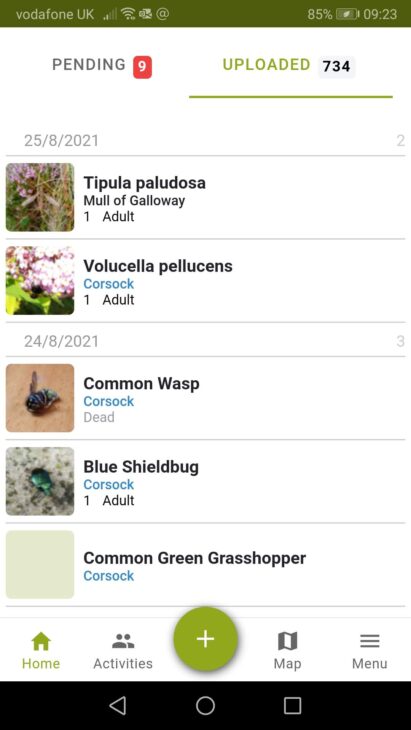

For users who wish to record a broad range of species, the iRecord app, launched in 2016, has become a popular way to enter records and share them to the online iRecord platform (brc.ac.uk/irecord) which houses over 16 million records, almost solely from the UK. Run by the Biological Records Centre (BRC) and designed specifically to support the UK wildlife recording network, the app allows entry of records across all taxonomic groups. It uses a dictionary of names (both English and scientific) from the UK species inventory to select from, so you shouldn’t have any trouble finding the correct species (or genus or family) for your record. If you use common names to enter records, do watch out for species which share the same name (a Redshank can be a moss, a plant and a bird!) and check the correct scientific name if you are offered multiple options. The app interface could perhaps be described as a little plain, especially when compared to some of the other apps mentioned below; however it works great for quickly entering wildlife records in the field, which is after all what it is designed to do. You can add a photo to support your record, which is helpful for record verification (see below), though is not essential (cf. iNaturailst below). The app has built-in OS mapping and aerial photos to refine the location of sightings and options for additional record information, such as life stage, are relevant to the species you are recording. Unfortunately there is no two-way flow of information from the iRecord platform back to the app, so you can’t get further information about the species you are recording, see any records you have entered directly on the iRecord website or view other people’s observations. Once uploaded, you can’t edit your records via the app – you need to log in to the iRecord website to make any changes. But as a simple app it works great as an efficient way to capture your records in the field and send them on so they can be used. For more information you can check out the iRecord user guide.

The other app for multi-taxa wildlife recording is iNaturalist. The app and the associated iNaturalist website (inaturalist.org) were developed in the USA and have a global remit, with over 79 million records entered worldwide. The app is linked to the iNaturalist database, and unlike the iRecord app you are able to see records from the database on the app – you can view, map and edit all of your own records, view local sightings by other users or even browse records from anywhere in the world. Data entry is simple, using the phones inbuilt information to locate and date the record. The app is particularly focussed on records that have supporting evidence, usually in the form of a photograph (although you can upload sounds too). You can enter records without a photo, but it’s worth knowing that these will generally not be shared onwards to other organisations. A major feature of the app, particularly for new or inexperienced recorders, is the ability of the app to suggest identifications for the pictures you upload. So for example if you take a photo of a moth on your window the app will give a suggestion as to what species it might be (or a genus or family if it is not confident). Whilst useful, this should be taken as a guide and certainly shouldn’t be relied on (see ‘Help with identification’ below). Overall the app provides a much richer community experience for the user, and is a great way to learn.

A key difference between the two apps mentioned above is how the records are checked. On the iRecord app, once entered and uploaded from your phone to the website, the data will go through some automated checks to flag records outside their known range or occurring at an unusual time of year. The records are then verified by local or national experts (all volunteers) who check records throughout the country. Verification coverage across taxonomic groups and regions is not 100% complete, but it is improving all the time and verified and unverified records remain available for anyone to use. In iNaturalist, the wider community of users does the checking, and those records where consensus is reached on the identification (where 2/3 of the people agree) are classified as ‘research grade’, and are shared onwards to national and global data repositories such as GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility). Records without any supporting evidence (i.e. without a photo or sound recording) are not checked by other users and thus never become ‘research grade’.

iNaturalist users can add observations without identifications (e.g. a photo of a flower and leaf can be recorded as unknown or simply ‘Plant’) and if a good photo is provided the community of users will help to formulate an ID based on the evidence provided. On iRecord users are encouraged to seek help with ID prior to submitting records (e.g. through some of the excellent online forums and social media groups) to avoid over-burdening volunteer verifiers with ID requests.

Another difference between the apps is the licensing and sharing of your records. If you use iRecord, all records are made available to the national recording schemes and local environmental records centres (LERCs) – this is part of the terms and conditions of using the site. On iNaturalist, you can choose a specific license for your records – the default license is attribution (must acknowledge the provider) and non-commercial, which unfortunately means that information may not be usable for some of the work that LERCs do. If you use, or plan to use, iNaturalist please see our post here to see what you can do to make sure your records are available for use by LERCs.

Species group apps

There are numerous recording apps which refine the cross-taxa approach to focus on a particular species group. Most use the same strengths of the smartphone – its inbuilt knowledge of who, where and when – to make record entry easy and some add on useful ID guides and detailed information about the biology and distribution of each species. Each uses a simple form to complete the entry of each record, or even a list of records. The BirdTrack app, managed by the British Trust for Ornithology, is a very popular tool for bird recording, and syncs with the BirdTrack website (bto.org/our-science/projects/birdtrack) which handles millions of bird records every year. Data entry is quick and efficient, and users can enter complete or partial lists (casual records) of their sightings at particular place. You can view recent sightings entered by other BirdTrack users, and it allows you to maintain your own year or life list. Other apps include Mammal Mapper (run by the Mammal Society) or those in the iRecord family such as iRecord Butterflies or European Ladybirds (BRC). These are submit-only apps – you send the data on to a central ‘warehouse’ but you can’t see the records of other users on the app – but each has excellent identification guides with plenty of photos, phenology charts and distribution maps to allow you to learn about the different species. Apple users also have the excellent iRecord Grasshoppers app available which has a good ID guide and recordings of the songs of as well as the usual record submission forms. If you are looking to record offshore then the Sea Watcher (Bangor University/ Sea Watch Foundation) and Whale Track (Hebridean Whale & Dolphin Trust, west Scotland only) apps allow you to record marine mammals and some associated species and both have excellent ID guides built-in.

Survey-specific apps

Some apps are specifically set up to support particular surveys or projects. These usually involve following a specified methodology (e.g. recording a specific area or for a specific period of time) and contribute more structured wildlife records which enable more detailed scientific analysis of the results. Examples include the FIT Counts app (Centre for Ecology & Hydrology – CEH), which records insect visits to flowers as part of the UK Pollinator Monitoring Scheme, and the NPMS app (CEH) which allows recording the results of the National Plant Monitoring Scheme surveys. The Big Butterfly Count app (Butterfly Conservation) supports the nationwide citizen science survey undertaken annually to monitor broad scale changes in the UK butterfly populations. The Mammal Mapper app mentioned previously also allows for more structured recording effort to be logged.

Some research projects may seek help from citizen scientists via their own apps to record or survey species or habitats, but it is always worth checking how the data are to be used and shared and how long the project will last. Records submitted to such surveys, whilst valuable for the particular project’s research, may not automatically be shared with the wider recording community and it may be worth checking with the relevant organisation about data flows and consider submitting important records gathered during such surveys through one of the main recording apps as well.

Help with identification

A small but increasing number of apps have incorporated an element of machine learning to provide help with identification from photographs or sounds. The iNaturalist app provides identification suggestions based on a photo and the location of the record, and in general these ID recommendations are fairly good. Where there is more uncertainty in the ID, the app will often suggest a broader genus or family. Another useful app for identification of photos is ObsIdentify (Observation International), which is an app related to a Dutch equivalent to iRecord or iNaturalist. The identification suggestions give a percentage likelihood and are usually very good. Bird song and call identification is the focus of the BirdNet app (Cornell Lab of Ornithology), which allows your phone or tablet to be used to sample and identify the bird songs around you. PlantNet is an similar plant-focused image ID app.

In all cases these auto-ID apps should be treated as guides or suggestions rather than definitive identifications, and they are by no means infallible, even when the suggested ID ranks highly. They can however provide very useful pointers for seeking out further information yourself and can be a great help if you are learning about a new species group. Particular caution should be used for difficult to ID species groups; some are simply not reliably identifiable from a photo alone (e.g. many spiders and fungi) where other characteristics may need to be checked (e.g. examining structures under a microscope) before ID to species level is possible.

Some tips for choosing which apps

If you have a specific interest in one particular taxonomic group, then the apps tailored to that group (e.g. BirdTrack, Mammal Mapper) may well be your best bet as they are tailored to provide useful information for that group. But if you wish to record a broader range of species, rather than having different apps for each one (if they exist) then a general app like iRecord or iNaturalist will allow you to keep all your observations together. You should also ask yourself what you want to achieve. If your goal is to make all your records (with and without photos) readily available to wildlife for use in conservation or decision making by national schemes and societies or LERCs like SWSEIC then currently the simple but effective iRecord is the best option for doing this. If you enjoy a more community-based approach, a more feature-rich app experience and some automated help with photo ID then iNaturalist is perhaps a better alternative – just remember that there are still limitations with data flows to into the UK biological recording network and any records you make without photos are unlikely to be shared. Apps to help with identification certainly can be useful, but don’t rely on them to get the correct ID – ultimately you still have the job (and the fun!) of identifying them yourself and hopefully broadening your knowledge at the same time.